Designing a Research-Based Programming Practice Interface

My Role: UX Designer, Full Stack Developer

Methods and Tools: Prototyping, Figma, Django, VueJS

The Problem

Learning to program comes with a unique set of challenges, including: learning to think logically/programmatically, using correct syntax, and mastering fundamental concepts such as variables and data types.

Most challenging of all, however, is that learners have to overcome many of these obstacles simultaneously.

The Process

Identify the opportunity

During his doctoral studies, my co-founder observed that very few educational tools existed which gently introduced learners to programming basics while also continuing to support them as they developed their confidence and expertise.

This was not to say that separate tools didn’t exist for programmers at various stages of skill; indeed, there were many. But none of them attempted to bridge the gap between novices and more experienced programmers.

Conceptualize a solution

My co-founder envisioned a programming practice tool that brought together all the different ways learners could practice their skills. His goal was to create a scaffolded educational experience that met learners at their current skill level and provided them with opportunities to gradually stretch their abilities.

There were 5 problem types he sought to combine, all rooted in computer science education research:

-

Pseudocode: Plain English descriptions of code blocks

-

Parsons Blocks: Mixed-up code blocks

-

Faded Parsons: Fill-in-the-blank mixed-up code blocks

-

Fix Code: Code that contains bugs

-

Write Code: Writing the code from scratch

Draw inspiration from the current landscape

As the UX Designer and primary developer for the project, it was my task to bring this vision to life; to synthesize these problem solving methods into a cohesive, intuitive, engaging interface that stood on the shoulders of prior research to offer a new-and-improved learning experience.

So first, I had to familiarize myself with computer science education research and the tools being developed in the field.

Pseudocode

The first problem type to incorporate was “pseudocode.” The concept was inspired by Kathryn Cunningham’s work on purpose-first programming, which focuses on the conversational aspect of programming. In her studies, she asks learners to spend time planning out the goals and subgoals of a program before diving into the code. Her findings conclude that “learning with purpose-first programming is motivating for conversational programmers because it engenders a feeling of success.”

Cal Poly’s Pseudocode Standard was another point of inspiration, as it provides a structured approach for describing code in human-readable English.

In our implementation, learners would drag mixed-up blocks of plain English code descriptions from an area on the left side of the screen, and place them in the correct order and indentation on the right:

Parsons Problems

The next problem type, Parsons Problems, was already commonly used with novice programmers. Popularized by an open source library, js-parsons, they are a staple in computer science education.

My co-founder’s own research finds that Parsons problems “usually improve problem-solving efficiency, lower cognitive load, and most undergraduates find them useful for learning how to program.”

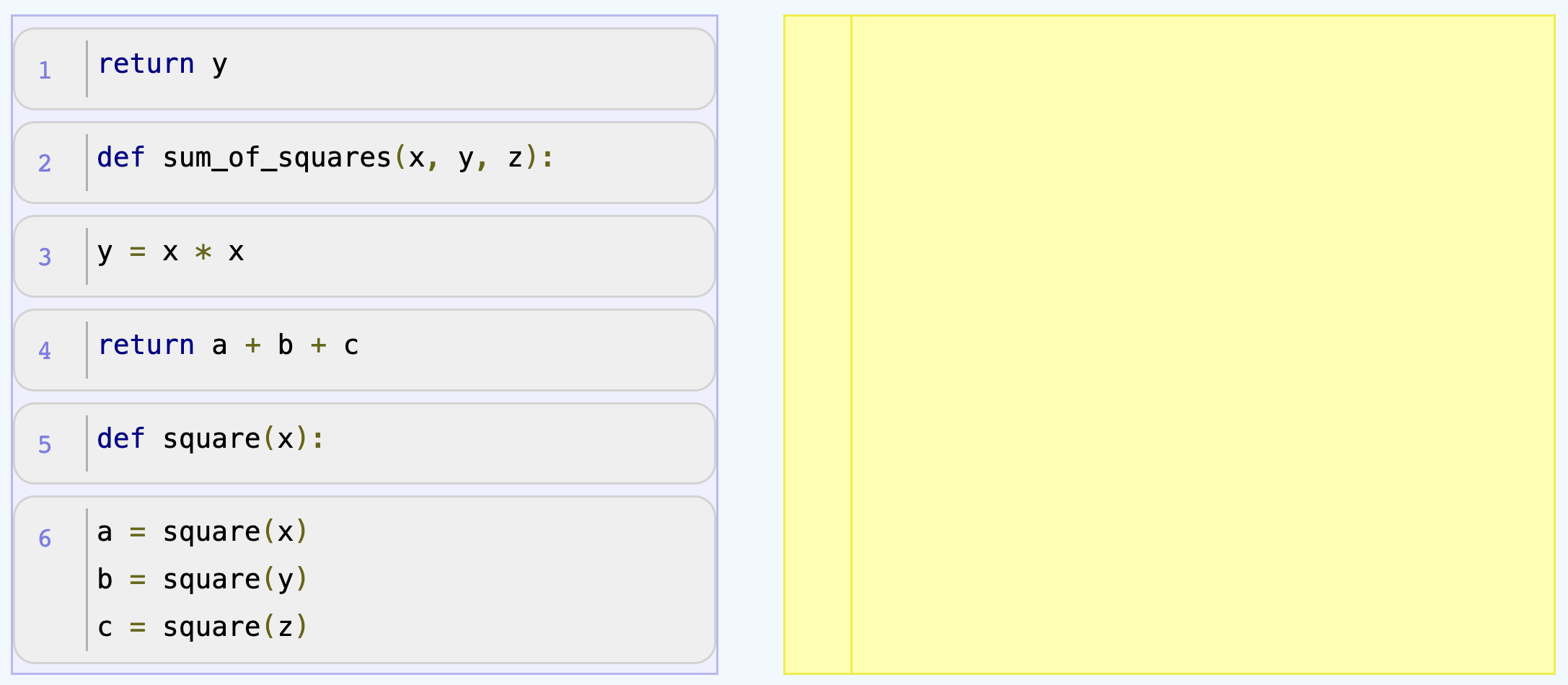

Learners start out with a set of mixed-up blocks of code on the left and must arrange them in the correct order/indentation on the right:

Our custom implementation of Parsons problems would work in much the same way, with one key difference: learners would have complete freedom to place a block at any x-y coordinate in the solution area:

Faded Parsons Problems

Nathaniel Weinman’s work on Faded Parsons problems (below) defined the 3rd problem type we wanted to include. He found that “rearranging and completing partially blank lines of code into a valid program, are an effective exercise interface for teaching programming patterns, significantly surpassing the performance of the more standard approaches of code writing and code tracing exercises.”

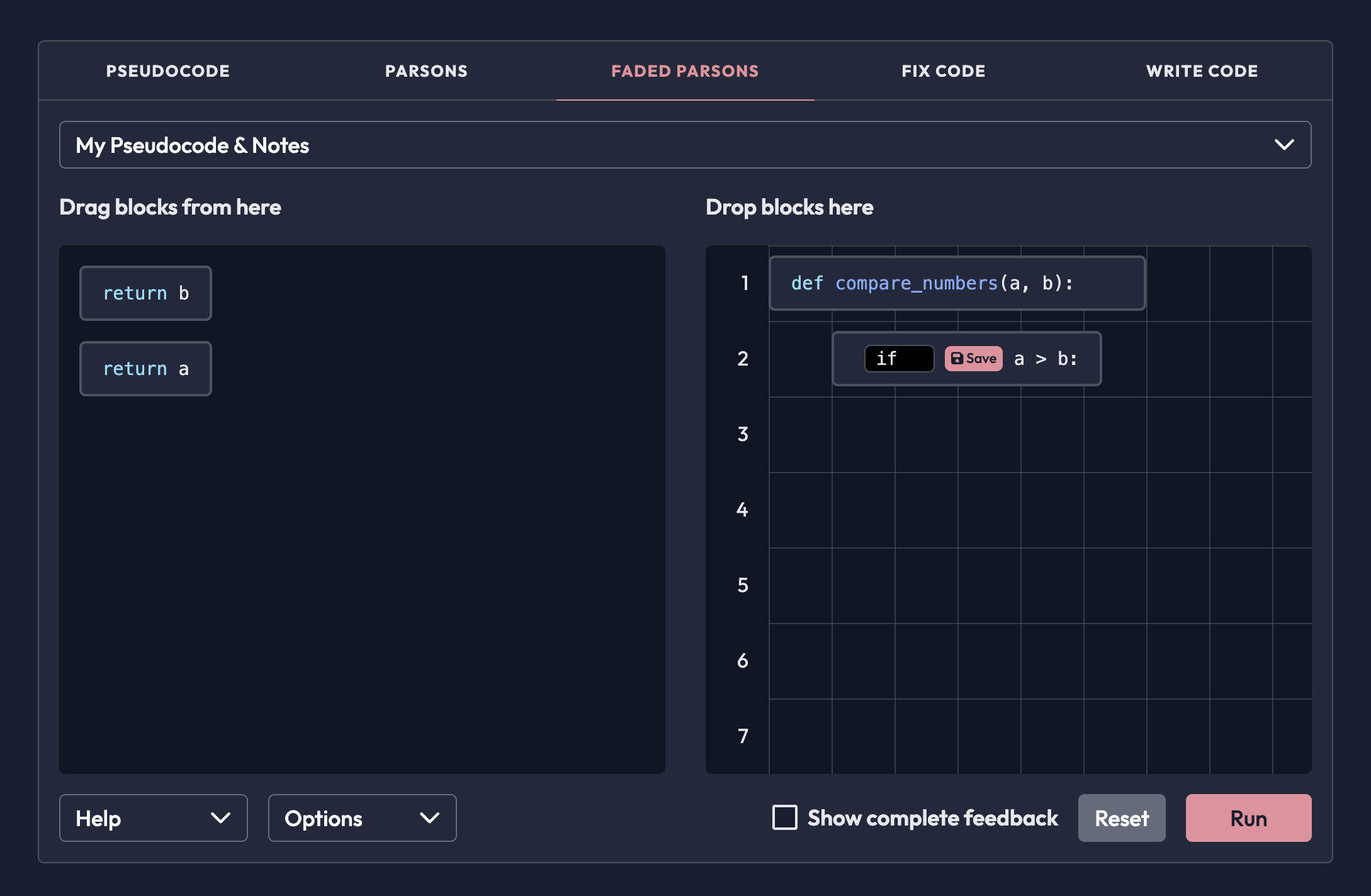

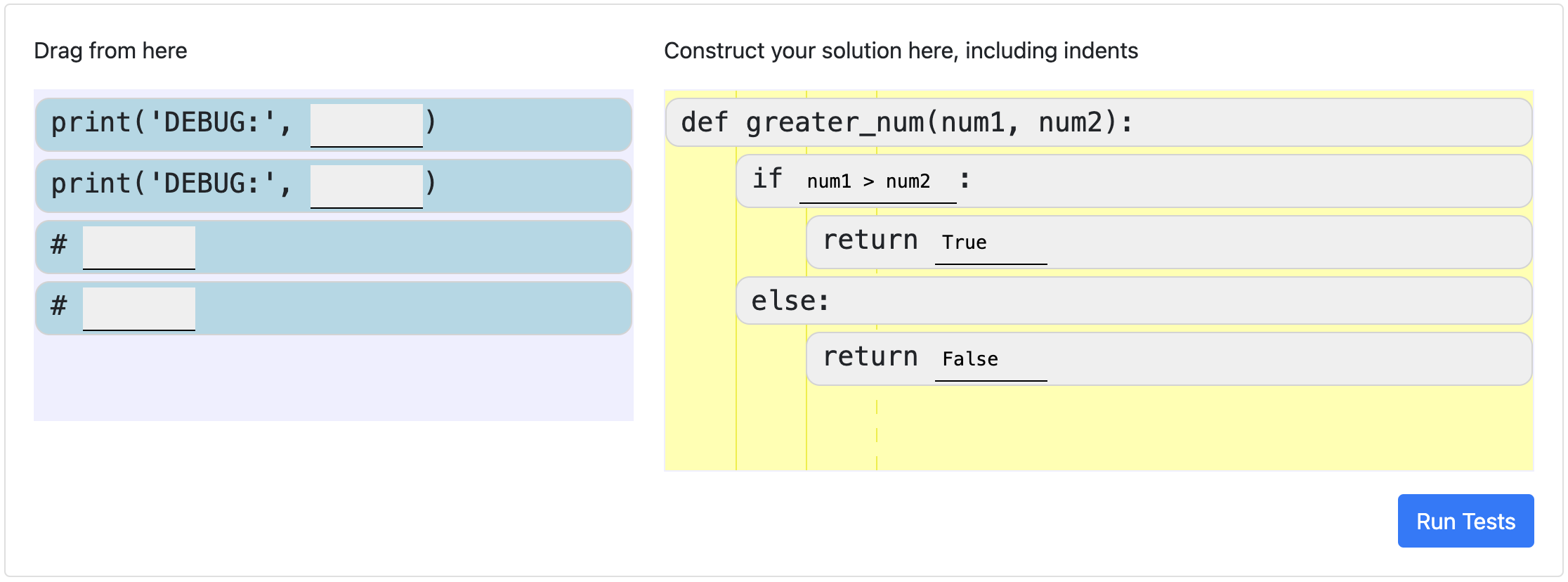

Our custom version of Faded Parsons problems would mirror the same style of text entry for fill-in-the-blank blocks:

Fix Code

Jacqueline Whalley et al report that debugging is an often under-taught, under-practiced skill and that many novice programmers wish they were equipped with better approaches.

Presenting learners with bug-ridden code and explicitly requiring them to debug it, therefore, seemed like a potentially beneficial exercise to offer:

Write Code

The ultimate goal for any programmer is to be able to write code on their own. So it was only logical to incorporate a completely open-ended IDE as the last problem type:

2022 Learning Levers Prize ($10,000)

After months of iterative design and development work, we had an initial prototype and were awarded a $10,000 grant from the University of Michigan School of Education’s Learning Levers Competition.

Since then we have continued to iterate on the platform’s design and data architecture, and add new features to support in-depth academic research such as workbooks, surveys and timed problems.

Next Steps

We continue to follow ongoing trends in the AI space and think about the role this technology could play in Codespec’s functionality.

Lessons Learned

Innovation takes many forms

Doing something new doesn’t always require creating a product that’s unlike anything people have ever seen. Sometimes it happens when you combine existing ideas in a new way.